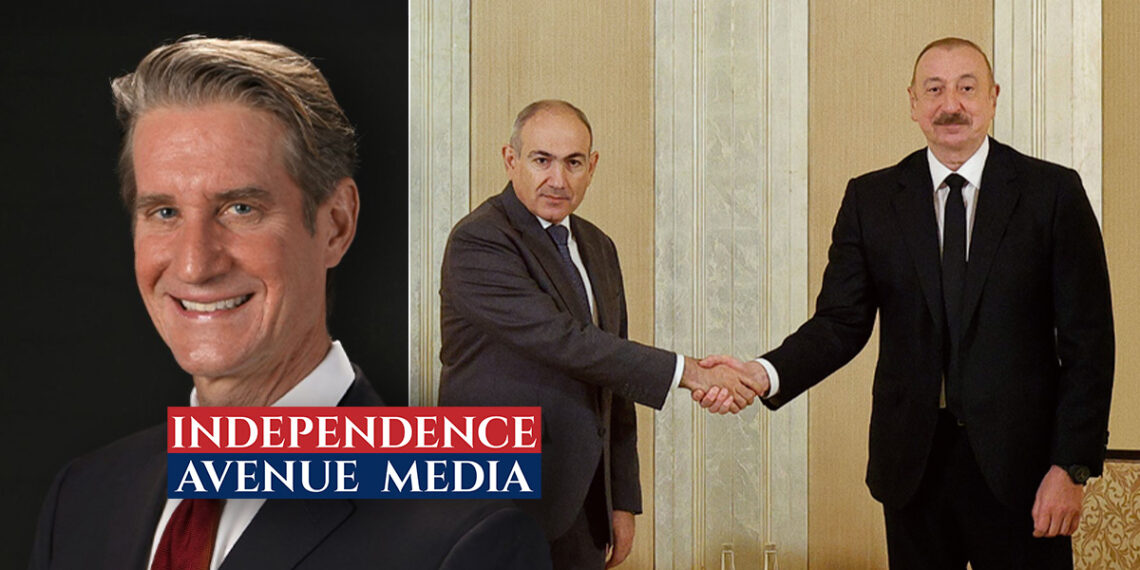

WASHINGTON, D.C. (Independence Avenue Media) – As the South Caucasus undergoes rapid political and strategic realignment, former U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan Matthew Bryza offers his perspective on what’s driving change in the region and what role the United States might play under President Donald Trump’s administration.

In an interview with Independence Avenue Media, Bryza reflects on the growing momentum toward a peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan. He discusses the implications of a proposed U.S.-operated transit corridor connecting mainland Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave through Armenian territory, suggesting that the plan is driven more by commercial interests than by strategic considerations.

Bryza, a veteran diplomat with decades of experience in the region, also discusses the retreat of Russian influence in parts of the South Caucasus, the recalibration of Armenia’s foreign policy toward the West, and Turkey’s expanding role as a regional actor.

He voices concern over what he describes as a lack of strategic coherence in Washington’s current approach, suggesting the administration’s foreign policy is driven less by long-term strategy and more by transactional opportunities.

The conversation also touches on Georgia’s uncertain place in this shifting landscape, as Bryza warns that the country’s democratic backsliding and strained ties with Western partners are eroding its position as a reliable bridge between Europe and the wider region.

The following interview was recorded on July 18, 2025, and has been edited for length and clarity.

Independence Avenue Media’s Kartlos Sharashenidze: Ambassador Bryza, thank you very much for your time. Today, we are looking at a number of important developments in the South Caucasus — especially between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and also in Georgia, which remains a key part of the region. All of this is happening while Russian influence seems to be weakening, at least in some areas in the South Caucasus. How do you see the overall picture? What’s really happening in the region right now, in your view?

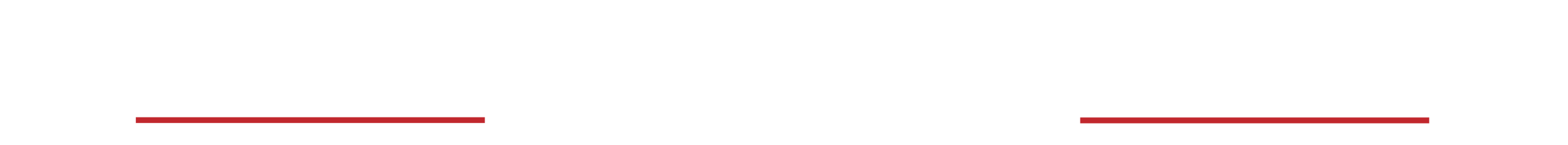

Former U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan, Matthew Bryza: First of all, thank you for having me. It’s a very, very broad question of course. So, I think that in general we see that Azerbaijan and Armenia are very close to a peace treaty. We see them trying to find a way to agree on, sort of the, the modalities of the Zangezur corridor. As observers know, the November 10, 2020, ceasefire statement — at the end of that phase of the Second Karabakh War — called for Russian FSB troops to operate the corridor and to provide for its security. I forgot the exact wording.

That was clearly a provision that neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia wanted. It was forced on them by [Russian] President [Vladimir] Putin. Now, the U.S. White House has proposed that the operation of that corridor could be conducted by a United States logistics firm. So, in other words, Russia would be completely out of that game. And I think that’s causing great consternation in Moscow — as well as heightening political tensions between Baku and Moscow.

That began with the shooting down of the Azerbaijani airliner by Russian air defenses last December 25, for which President Putin never apologized or even acknowledged culpability. That has really angered [Azerbaijan] President [Ilham] Aliyev.

So, we see Russia, definitely, as you were saying, either on the retreat or being forced to move backwards with, the U.S. and Europe — particularly in Armenia’s case, Europe — are strengthening its role. I don’t think the U.S. under President Trump seeks a big geopolitical role in the region. I think it’s looking for business deals. President Trump wants a Nobel Peace Prize, and he hopes he can play some role in being there right at the very end — like the guy who jumps to the front of the parade at the last minute — as Azerbaijan and Armenia reach a peace agreement.

As for Georgia, it’s in crisis. And it is no longer what it was. It is no longer a European country that is marching toward membership in the transatlantic community. It’s not. It’s stuck. And that is by Russia’s design — and, of course, with a lot of help from some people in Tbilisi.

Sharashenidze: You’ve already covered almost everything I was planning to ask. You mentioned the so-called Zangezur Coridor. So, Let’s talk more specifically about Armenia–Azerbaijan relations. We’re now seeing efforts to end decades of conflict — and at the same time, the two countries are starting to work on economic progress and better regional connectivity. How did this become possible? And what does it mean for the wider region?

Bryza: Well, the corridor is long overdue, right? Five years ago — going on five years ago — President Aliyev and Putin and [Armenian] Prime Minister [Nikol] Pashinyan declared that all transit links are open and that there would be this corridor through Armenian territory to connect the main part of Azerbaijan with Nakhichevan.

It’s taking much longer than anybody had hoped. That’s because it’s also taking a longer time to negotiate the final elements of a peace treaty. But the recent acceleration of these developments, I think, was launched back in March, when the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia announced they had finalized the text [of the treaty].

There were a couple of issues left — but one is quite significant, which is Azerbaijan’s insistence, understandably, that Armenia’s constitution does not contain a provision suggesting that maybe Karabakh is not part of Azerbaijan. On the other hand, it’s very difficult for a country to amend its constitution at the behest — or demand — of another country, much less one with whom you just fought and lost a war.

So, Prime Minister Pashinyan is clearly committed to getting that amendment through his political system, through his parliament. It’s a difficult battle. But let me put it this way — an Armenian senior diplomat told me just a week and a half ago that he’d been working on the Karabakh conflict for almost 25 years, and he said: “We — meaning Armenia — we have never been this serious about peace.”

And in Baku, they’re also saying, “We are very, very close.” So, against that backdrop, it makes sense that there’s movement on the Zangezur Corridor.

I think the point about Russian FSB troops maybe not having a role — Russia being pushed back geostrategically — is a result of two things. One is what I already mentioned: President Aliyev’s anger at President Putin over shooting down the aircraft and the lack of apology — not to mention damages.

But on the Armenian side as well, since the Second Karabakh War, Prime Minister Pashinyan has been leading Armenia more and more toward the West — more and more toward Europe. As we know, Armenia is going to withdraw — if it hasn’t already — from the Eurasian Economic Union. The military cooperation between Armenia on one side and the U.S. and EU on the other side has just been increasing for the past few years.

Sharashenidze: Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan said Armenia might be open to a U.S. company managing transit through the so-called Zangezur Corridor. What kind of U.S. presence would this be in the South Caucasus? And what would this mean not only economically, but also for regional security?

Bryza: Well, first of all, I was really surprised to hear that proposal from the Trump administration, because the Trump administration has not shown any real interest in the conflict — although Steve Witkoff, [President Donald] Trump’s top envoy, did visit Baku several months ago. I forgot exactly when that was, but it was never explained why he was there.

The Trump Administration does not think geostrategically. It thinks about transactions. It thinks about deals for U.S. companies. So, when U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Tom Barrack announced this proposal, it made sense to me in terms of a U.S. company would get a business deal, and that company would be acceptable to both Azerbaijan and Armenia — because there wouldn’t be Russian security services running the corridor.

But the problem is, what Ambassador Barrack announced is not really acceptable to either Armenia or Azerbaijan — in terms of a U.S. company getting a 100-year lease on the corridor itself.

That approach makes sense if you’re a real estate developer like Donald Trump or Steve Witkoff. They think [in terms of] wanting to build a building, okay? They can either own the land, but you can’t own the land of another country, or they can lease it. From a businessman’s perspective, that’s smart. From a diplomatic perspective, that’s not smart.

It’s impossible for Armenia and Azerbaijan to agree, because part of the corridor will be on Azerbaijani territory as well, that after these two wars, after a peace treaty that’s just around the corner, to say, okay, we’ll allow an American entity to have possession of our land.

Now, you could argue a lease is not the same thing as a change in the sovereignty of the territory. But a lease does mean less sovereignty of the country over the territory. There’s no way around that.

So, I think what happened was that the Trump administration, it doesn’t have the staff that the U.S. presidents normally have to think through these proposals to coordinate them with all the various pieces of the government to understand where there might be some weaknesses, where might there need to be some adjustments. They didn’t do that. It’s just a small group of people who develop real estate to make a fortune and they say, well, we’ll treat the corridor like a piece of real estate. That just will not work for two countries that just fought a war over to whom this very territory belongs. I think this will get worked out, though – whether you call it a lease or some operational agreement that can be negotiated.

Sharashenidze: As I understand it, you see this more as a business deal rather than a political or geopolitical step from the U.S. administration? Because there’s this perception that when major U.S. companies are present on the ground, it also brings some kind of political or broader security guarantees.

Bryza: I very much, agree with you. You said that the countries, people in the countries – in Azerbaijan – hope that a business deal like this would bring along some U.S. security guarantee. The Trump administration has suggested that in the case of Ukraine and the minerals deal, when [Ukraine] President [Volodimir] Zelensky was very eager for a clear U.S. statement of security support for Ukraine, the Trump administration said: “Well, give us the business deal to have access to your critical minerals, and that’s your U.S. presence — that’s your security guarantee.”

But that’s not how the world works.

Look at Cuba. In 1959, there was a revolution. All the U.S. companies got nationalized. A brutal regime came to power. The U.S. did really nothing — they tried to overthrow Castro with the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Then we got the Cuban Missile Crisis, and for the subsequent decades, Cuba just kept operating as it had been since 1959, with the U.S. companies kicked out.

So, in other words, if there’s a radical political change along the Zangezur Corridor, it’s absolutely conceivable that the U.S. company running logistics could be kicked out — and there would be a whole new security situation.

To counter that pessimistic view, though, I will say: if there is a U.S. company that’s close to powerful people in Washington, that’s on the ground with U.S. personnel, earning money for a U.S. company — then presumably, the Trump administration will at least pay attention to Armenia and Azerbaijan.

But from my perspective, no. A business investment is in no way a security guarantee or a sign of some sort of U.S. military presence.

Look at Saudi Arabia. The Saudis nationalized U.S. oil companies as well and there’s no U.S. military presence in Saudi Arabia. Maybe there will be. There are negotiations under the Abraham Accords, potentially, if Saudi Arabia normalizes relations with Israel. But in that case, there would be an explicit security guarantee by the United States — and not just a suggested guarantee because the U.S. has investments in the country.

Sharashenidze: What about Turkey? Turkey is an important player in the South Caucasus and a close ally of Azerbaijan. What impact does Turkey’s involvement have on the balance of power and security in the South Caucasus, especially considering potential U.S. presence in the so-called Zangezur Corridor?

Bryza: Turkey has a huge economy, a broad and deep industrial base. It has NATO’s second-largest military. It borders Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as Georgia — and also Russia and Ukraine across the Black Sea. And, as we know, Iran, Iraq, and Syria to the south. So, it’s an incredible piece of real estate with a huge economy and military. So, it’s consequential.

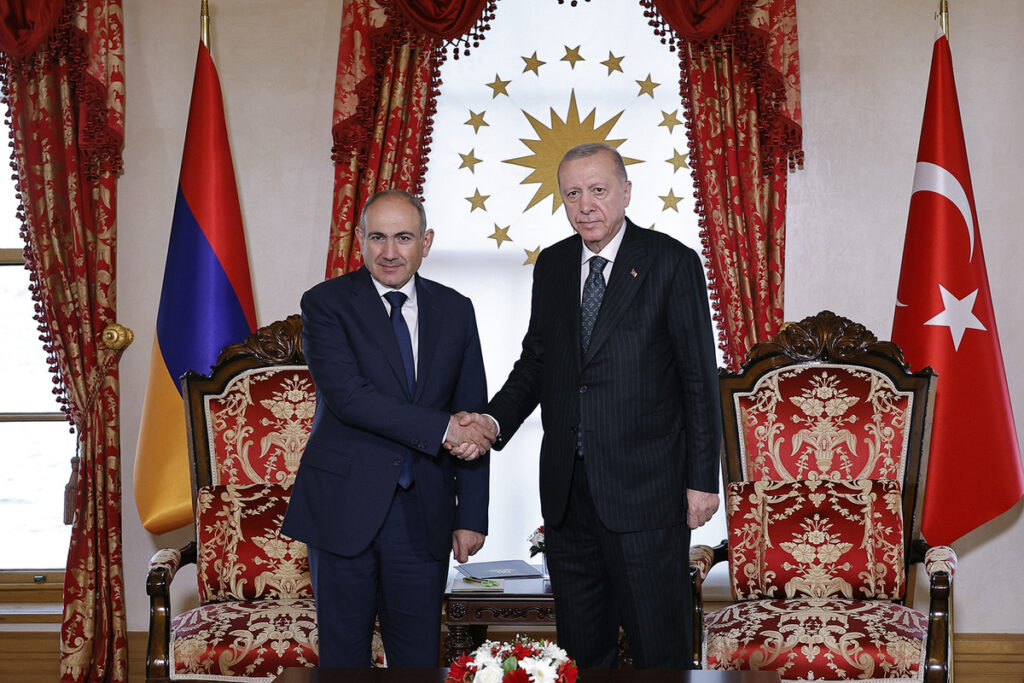

Historically, Armenia has looked for protection against Turkic states and looked to Russia [for this protection]. But that’s changing now, as we discussed at the beginning of this interview. It seems President Erdogan and Prime Minister Pashinyan have developed a nice relationship. Pashinyan just visited Erdogan in Istanbul. The two leaders really seem to get along.

That’s a new dynamic in the Armenia-Turkey normalization process. You’ll remember in 2009, the two countries signed agreements to normalize relations — and then their parliaments never ratified them.

When it comes to Azerbaijan, the cliché goes: “one nation, two states.” The two countries have a military alliance — which sounds like a pledge by each country to come to the other’s aid if attacked militarily. So, you couldn’t have a closer relationship than what exists between Turkey and Azerbaijan. So that’s a big role for Turkey already.

Turkey is at one end of the Zangezur Corridor. Once that corridor is built, I think we’ll see significant investment from Turkish businesses — in transportation, natural gas pipeline, manufacturing, all along the corridor.

And then also, we should keep in mind that, further down to the eastern side of the Zangezur corridor are more Turkic states. Turkey has created the Organization of Turkic States as a cultural, economic and political grouping, that draws upon the cultural ties of the Turkic states.

The Zangezur corridor will be right in the middle of all that. This is a moment of Turkey’s increasing geopolitical significance, and it has a chance to play a role that President Erdogan believes Turkey can play, but many other countries don’t agree. Erdogan views Turkey as a stabilizing force that can help bring peace, prosperity, and justice… after all, the name of his political party is the Justice and Development Party.

Sharashenidze: What do you think Russia’s response might be to these developments?

Bryza: Russia doesn’t really have the military wherewithal — or the will — to intervene militarily and go to war with Azerbaijan and Armenia. It’s not going to happen. It can’t do it. It doesn’t have the capabilities now – number one.

Number two — we’re seeing a different kind of response from Russia. One is to move more troops, it claims, to Gyumri — although the Armenian government has denied that that happened. The other is the increasing political tension with Azerbaijan which, who knows, maybe aims at creating political instability in Azerbaijan, I don’t know. Or is it just the angry dispute between the two leaders? I’m not sure.

But I think Russia has been turning up the tension with Azerbaijan, and one reason is probably to try to intimidate Baku as it moves away from Russia geopolitically.

Sharashenidze: How do you see Georgia’s role in the South Caucasus today? What risks or opportunities might this shifting landscape create for Georgia?

Bryza: Georgia already is the existing component in the South Caucasus and the Middle Corridor. But it’s less and less interesting to Europe and to the United States.

It’s not on the path of association with the EU. It’s seen no longer as a normal member of the transatlantic family — possibly — or even a member of the European family. Its government has said it will suspend this association effort.

The EU has imposed sanctions and made clear that they do not consider the current Georgian government friendly. I think the Georgian government feels the same way. Also, there’s a good possibility that Georgian citizens are going to lose their visa-free travel ability to the European Union. So, Georgia is playing itself completely out of the European geopolitical game and completely into Russia’s orbit.

When Georgian leaders say ridiculous things like “the U.S. and Europeans are trying to open a new front and bring Georgia into the war,” it is such an obvious lie and bit of anti-Western propaganda that it shows that the government is a puppet of Moscow.

Nobody wants to deal with a government like that. It’s not trusted. So, who’s going to invest in Georgia under those circumstances? Nobody. Nobody.

Georgia is on a downward spiral. It’s a country I love so deeply, and you do too. It’s hard for me to say these things, but so much of what Georgians have achieved is being broken. It’s very difficult to repair and very easy to destroy.

Sharashenidze: With all these changes in the South Caucasus, what should Washington’s strategy be moving forward? What role can — or should — the U.S. play in shaping the future of the region?

Bryza: In terms of U.S. policy toward the South Caucasus, I simply believe there needs to be one. There is not one.

President Trump does not have strategic vision. There are professionals — like I used to be — inside the State Department and Pentagon who, of course, want to continue with the longstanding U.S. approach to the South Caucasus, which is to encourage them to strengthen their ties to the transatlantic community, help them prosper economically, help move the natural resources to global markets, bolstered democracy and political and economic freedom. That’s a great overall policy, but I don’t think President Trump has that view.

He doesn’t have an apparatus, a mechanism like has always existed since the end of World War two, based around the National Security Council staff, that coordinates policy ideas and make sure that every element of the U.S. government, every department is heard, can debate, can make its views known, can argue, and that a coordinated policy recommendation comes out that the president can either accept or change. That doesn’t happen anymore, there is no such process.

So, what I criticize is that there’s no systematic approach to foreign policy by the Trump administration. It is very unpredictable and the notion of the U.S. friends and foes is very strange for me.

President Trump was clear during the election campaign saying that, he will treat as a friend a country with whom the U.S. has a trade surplus, and he will treat as a foe a country with whom the U.S. has a trade deficit. That is completely different from any U.S. foreign policy approach — ever.

I think it’s gravely unwise and it’s not even consistent. Because right now, President Trump is talking about 50% tariffs on Brazil due to a political legal issue [related to] the treatment of former President [of Brazil Jair] Bolsonaro. But the U.S. runs a trade surplus with Brazil. So, there’s just no consistency.

That’s what I’m critical of. It’s the amateurish, haphazard, non-strategic foreign policy and that’s bad for all of us.