WASHINGTON (Independence Avenue Media)—Russia’s war on Ukraine is poised to stretch well into 2026, with no ceasefire in sight, warns George Barros, a top analyst at the Institute for the Study of War. In a detailed interview with Independence Avenue Media, Barros outlines the widening gap between battlefield realities and Western strategic planning, urging a sharper U.S. and allied response to avert an even larger conflict.

Barros says the recent delay in weapons shipments may not have changed the tactical map, but it exposes a lack of consistency that undercuts Ukraine’s ability to plan counteroffensives. The Kremlin, he argues, is wagering that it can outlast Western resolve—not through military superiority, but through erosion of Western political patience and credibility. He argues that consistency, timing and clarity are everything as it comes to Ukrainian military planning.

The Russian summer offensive, while slow-moving, continues to grind forward at great human and economic cost. Russia’s current force-generation model—the monthly recruiting of tens of thousands of men from the country’s poorest regions with financial incentives—is unsustainable, Barros argues. Yet without decisive Western policy to force Russian President Vladimir Putin into difficult choices, the Kremlin may remain unchecked in its slow-burn campaign.

Barros draws parallels to the late 1930s, warning that the world is on the brink of a far larger war. He points to a growing alignment between Russia, China, and Iran—states bent on reshaping the global order—and urges Western leaders to see the conflict in Ukraine not as a regional war, but as a frontline in a systemic confrontation. “A larger scale war is on the horizon, and we need to act decisively to deter it,” he says, as the West might otherwise be forced into a conflict on terms it didn’t choose.

The following interview was recorded on July 9, 2025, and has been edited for length and clarity.

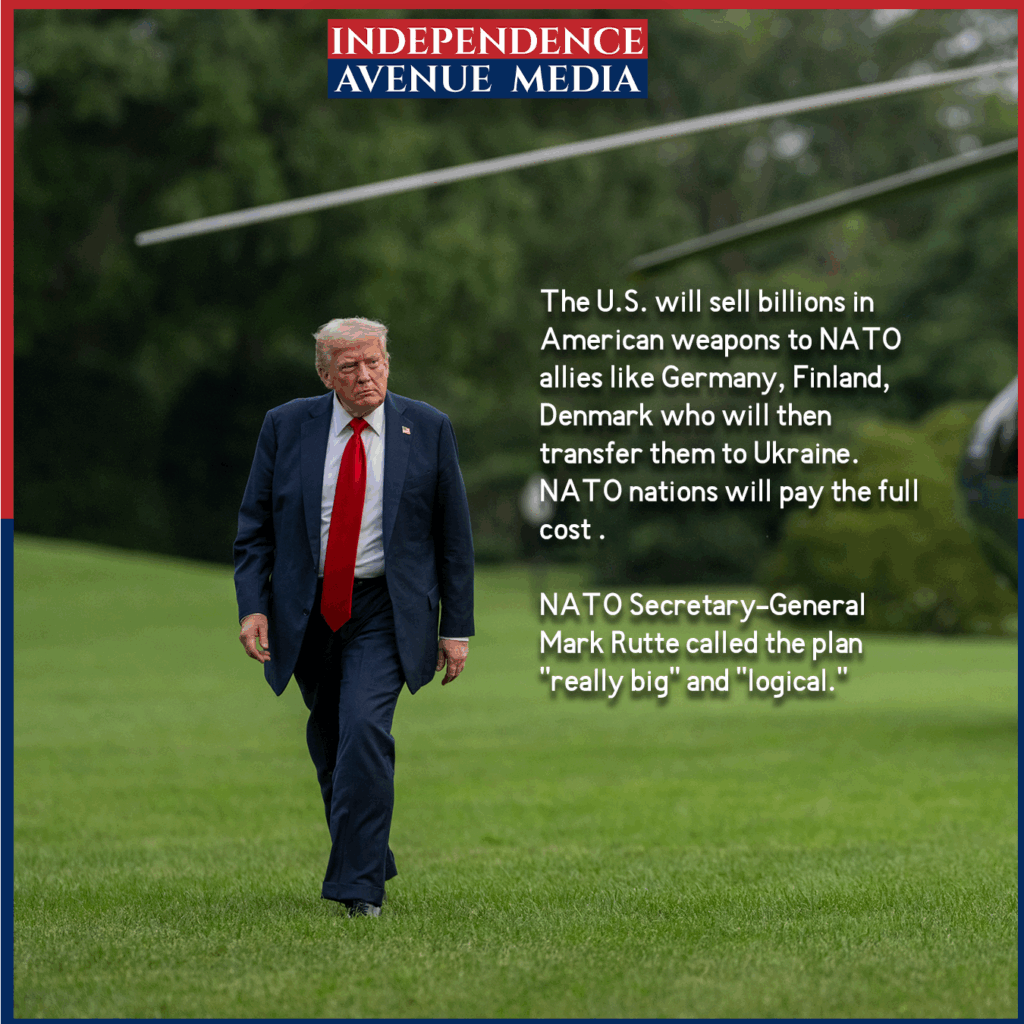

Independence Avenue Media Editor in Chief Ia Meurmishvili: As viewers know, the U.S. had paused arms shipments to Ukraine for a few days, but then yesterday we heard that President Donald Trump said that the U.S. will resume weapons supply and ship these weapons. What impact do you think the pause has caused—even if it was not a long pause—and what impact do you think the shipment or resumption will have?

Russia Team & Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT) Team Lead George Barros: The shipment that was paused in Poland by itself was a fairly small shipment and the delay that it had there probably didn’t have a very substantial battlefield impact. Every time that the Ukrainians do not have Patriot interceptors—and there were 30 Patriot interceptors in that paused shipment in Poland—that does degrade Ukraine’s ability to intercept, Russian ballistic missiles in particular. But in terms of the battlefield front line, in terms of [a given military] unit’s ability to sustain themselves and maintain their tactical frontline positions, I don’t think that the pause likely, decisively affected that. Now, that’s at the tactical level.

On the strategic level, however, Ukraine needs substantial military assistance in order to sustain what has become a protracted war, the reason being that Putin’s theory of victory is that the Russians can, in his assessment, overtake Ukraine not through excellence in the battlefield, not through a professional military, but simply outwaiting Western support [and] outwaiting Western patience.

In order to be able to get to the negotiating table and not just be ground down, Ukraine obviously has to reverse some of these Russian battlefield gains. That has a presupposed requirement of the Ukrainians. At some point in time, they have to conduct some tactical counterattacks; they have to plan some counter offensive operations to change Putin’s logic for why he can’t just, in time, cease all of Ukraine, even if it takes many years.

In turn, that requires consistency from the United States in the aid that we provide—and consistency not just in quantities but timing. Because as a Ukrainian general, it’s exceedingly difficult to actually plan counteroffensive operations if the materials, even if they’re small or in transit, can’t be relied upon because it’s always changing.

So, it’s a good and positive thing that the aid is being resumed, and that the Trump administration appears to be going through a little bit of a re-evaluation of its policy on Russia and Ukraine. We just recently had some unprecedented statements from President Trump. Having been through brute force [negotiations] with the Russians face to face for the past six months, I think he’s realized that the Russians are not interested in negotiation. The Russians are committed to achieving their battlefield objectives and that, therefore, conflict termination presupposes defeating the Russians on the battlefield. I’m not going to use the word optimistic, but I remain hopeful that this administration will start leading into different policies, which include using the minerals deal to get more weapons sales to Ukraine.

Meurmishvili: President Trump basically underlined that the weapons the U.S. is sending will be defensive. What does that mean to you—do you read anything into it?

Barros: When we talk about military systems, I really don’t like the adjective defensive or offensive because almost every single weapon system—perhaps with the exception of landmines or maybe a moat around a castle—can be used in both an offensive and defensive capacity. I think policymakers and politicians tend to like to add those adjectives before words to make it a little bit more palatable. It’s really a rhetorical device, which I don’t think is particularly appropriate in military studies or military science.

That notwithstanding, it tells us that President Trump is indeed going through a policy inflection. His previous position was that we’re not sending more weapons, and that the weapons we would send would just be the continuation of the previously approved Biden administration PDA [Presidential Drawdown Authority] aid. Now, when we have this inflection, which is we’re going to send them more weapons, even if he has to put the word “defensive” there, that’s a good thing.

Meurmishvili: Russia’s summer offensive is underway. We are getting conflicting reports on the advances from both sides. What’s your assessment?

Barros: This summer offensive has been underwhelming, [although] the Russians do make small-scale tactical gains every single day. We (ISW) are mapping the control terrain and every day we can verify that the Russians advance a couple hundred meters here and there. They seize the field, they seize a village, perhaps a couple villages a week. But in terms of the standards and the norms of modern mechanized warfare, this is a very slow pace. The attrition rate is not in Russia’s favor.

The Ukrainians are successfully inflicting a very high attrition rate on the Russian forces. These gains that the Russians make on the map—where over the course of weeks and months they can push the map forward—they do that at the expense of destroying Russia’s demographic situation and eroding the basis of Russia’s economic prosperity and economic stability. And it seems that the current tradeoff is not particularly stable or sustainable if we continue keeping the Russians at this current attrition rate.

Meurmishvili: How about manpower? Russia has not had any large-scale mobilization since the fall of 2022. Since then, Russia has basically been bribing its own population from some of the poorest regions of the country to recruit manpower for the war. It’s been over three and a half years of this war. How sustainable is this approach? How much manpower can Russia generate? How much longer can Russia continue doing this?

Barros: That’s an excellent question. If I could tell you the exact month or day or hour that it would happen, then this would be very simple. It would simply be an algebra equation for how to outlast the Russians. It’s never quite that simple because a lot of factors go into that.

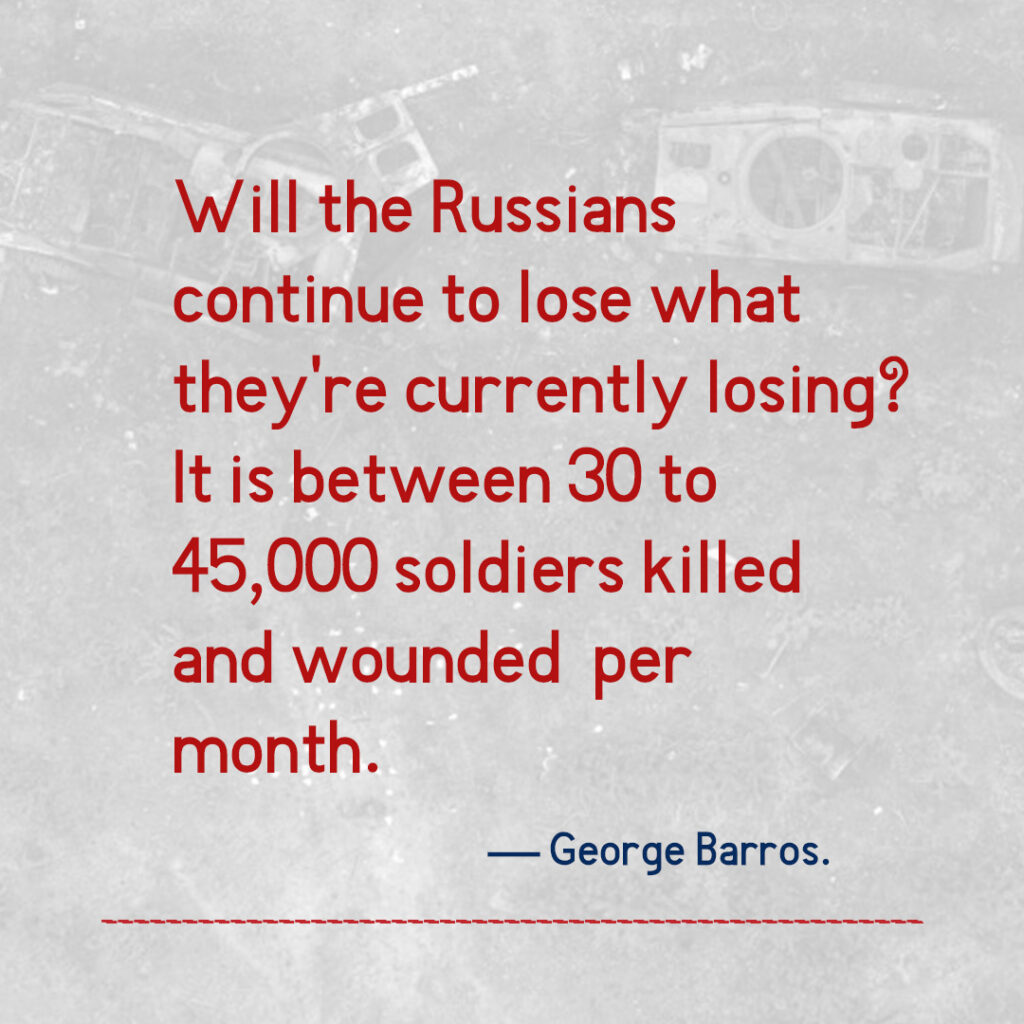

The biggest and most decisive factor is: what is the attrition ratio? Will the Russians continue to lose what they’re currently losing? It is between 30,000 to 45,000 soldiers killed and wounded per month. Now, if the attrition ratio goes down—perhaps because Western support for Ukraine decreases, or perhaps because the Ukrainians become much less effective in their fighting—then the Russian ability to sustain and protract the war will in turn go forward. So, one of the most important things is to nail down as many of the unknown factors as possible—that is, to be sure we can count on Ukraine’s ability to continue extracting the very high casualty rates against the Russians at the current tempo.

In terms of Russian force-generation and recruitment, all of the open-source data suggests the Russians are recruiting somewhere in the neighborhood of 40,000 to 45,000 troops per month—perhaps a little bit higher than that. But exactly as you noted, Putin is bribing his own population and spending on each volunteer that goes and fights in Ukraine a tremendous, luxurious compensation package, which is fundamentally not sustainable for a long-protracted war.

I think this would have been a good model and it could have been a workable model if you’re fighting the two-week “special military operation,” or perhaps a war of a couple months or maybe even a war of a year, but certainly not a war of three, four, five years plus.

Look, we can talk about all the economic externalities that the Russian payments have created. Inflation is extremely high because you have a country that’s flush with cash due to both just the one-time sign-up bonuses, but also all the other salaries and benefits. You have, therefore, very high money supply. You also at the same time have a very high interest rate from the Russian central bank at 20%, which should actually really be higher. Of course, this causes problems for the financial and banking classes.

Russia’s military industry actually needs to have the cost of capital be lower in order to have the capital availability to continue producing tanks and weapons and things at scale—all the stuff that [Russia’s state-owned defense conglomerate] Rostec is doing. Then, of course, you also have the issue of the labor shortage, because we had 700,000 Russians flee in 2022 from the initial round of mobilization. You now have an estimated one million Russian casualties from the war, and every month they are losing [soldiers] but also recruiting about 45,000 men. The reality is that with this current labor shortage of about a million workers—soldiers, able-bodied men—they can either fight in uniform in Ukraine or they can work in the domestic economy and contribute to GDP. But you can’t do both simultaneously. And the dead and wounded do neither.

Putin can call another round of mobilization if he really needed to. He really prefers not to, because it would violate Russia’s social contract. But if he does [issue another call], it will come at the expense of the Russian labor market and the labor pool. He has the option to go and recruit more workers or fighters from Central Asian countries or go to the North Koreans. But that also has implications for Russia’s domestic situation.

The key thing here is that there really are no good options for the Kremlin. They have to keep muddling through this issue. Our proposition is as follows: We have insulated Russia from having to face tough decisions because we have refused to put Russia into very precarious positions. We should actually instead try to force a buffet of bad options on Putin where he has to make difficult choices. And with those [difficult choices come] intrinsic risks. And, actually, we are more likely to get to the negotiating table or defeat the Russians on the battlefield if we have to invalidate some of Putin’s assumptions—if we have to push Putin to make difficult decisions, which might not decisively break his war machine but force him to have to make these hard choices. Because Putin, when given hard choices, actually has a pretty iffy track record. He makes mistakes all the time.

Meurmishvili: What would be some of those bad choices?

Barros: Does he call another round of mobilization and violate his social contract with the Russian population? [That] is, “I pay you, I don’t force you to fight.” That would be a bad choice from a social contract perspective. It would also [force] a bad choice between prioritization of the labor market and domestic production versus fighters in Ukraine. Obviously, when you pull 300,000 reservists, those people have jobs. They’re not pensioners. They’re working somewhere, which causes problems.

He also maintains the option of increasing payments for soldiers to try to increase the volume of volunteers. That has been the historical model that they’ve gone with. And, as we saw in recent months, Samara Oblast is offering up to four million rubles as a one-time sign-up bonus just to go fight. It’s about $40,000. That’s life-changing money for the average Russian.

It used to be that each individual Russian federal subject would do their own recruiting for their own population. But then they started to open it up and had them compete against each other. So, Samara Oblast could have tried to attract people that were living in Rizan or Kazan or other oblasts as well.

Meurmishvili: Do you think the U.S. strikes on Iran and Iran-Israel war has had an impact on Iran-Russia relations? In particular their military relations and impact on the battlefield?

Barros: At this time, no. We have not seen a reduction in Iranian-produced “Shahed 136” drones across the theater. In fact, some of the most intense Russian strikes, with some of the highest number of Iranian-sourced drones, have been since after the Israeli strikes. The reason is because the Iranians, through a technology transfer, helped the Russians indigenize the production of these Iranian drones in Russia’s Tatarstan region. My understanding of those facilities in Tatarstan is that they’re actually quite self-sufficient. When the Israelis damaged a variety of military production infrastructure within Iran, that did not degrade the Russian capability. In hindsight, it’s a major strategic mistake that the West did not act sooner to try to prevent the Iranians from doing this technology exchange. Because the Americans can strike what we strike in Iran. We are obviously targeting nuclear facilities. The Israelis can strike things that they want to strike in Iran. But if the Iranians have established and planted production capabilities within Russia, that’s a location that we are politically unwilling or otherwise unable to strike.

Meurmishvili: Is it known where those factories are?

Barros: Yes, they are known. There’s a place in Tatarstan called the Alabuga Special Economic Zone. The Ukrainians actually have targeted it numerous times in the past, so they have damaged some of those facilities. But it’s very large and they’re protected and they’ve been reconstructed and repaired since then. It’s a regular target of the Ukrainian long-range strike program.

Meurmishvili: Where do you see this war going? Recently you said that we will not have a ceasefire this year. Do you anticipate the war to keep on going for another year or so?

Barros: It’s my assessment that this war will continue for a long time because the negotiating positions of the belligerents are too far apart from each other.

Having a negotiation presupposes that both sides actually have some common goal that they can work towards in part. And [instead] what we see is Russia’s official negotiating position: that you must have regime change in Ukraine. You must have Ukraine denude itself, demilitarize itself, and the Ukrainians must cede a minimum of four provinces that the Russians don’t fully control—Zaporizhia, Donetsk, Luhansk and Kherson. That is an extreme non-starter negotiating position because there’s no reason for the Ukrainians to cede major population centers and geo-strategically significant territory that the Russians don’t own and are unlikely to actually seize any time in the near future, given the very slow rate of Russian advance.

The Ukrainian position is, of course, that they want to retain their territory, retain a strong military, retain their sovereignty, retain the strategic territory that’s needed to defend the rest of their state. These are incompatible positions. What we’ve seen over the last six months has been an effort in the United States to try to get the parties to negotiate. Even this administration has acknowledged that the negotiating positions are too far apart, that they’re not going to get there and now we seem to have an American reevaluation of policy vis-a-vis Russia.

We are going to keep fighting the rest of this year, and the belligerents will likely keep fighting the rest of next year. And it’s hard to see the forecast going beyond that, but I’m fairly confident that, until we actually change Putin’s logic for why he shouldn’t just continue doing a slow steamroll of Ukraine, then he will have no incentive to achieve what he wants.

Meurmishvili: You argue that the world, at the moment, is at a stage of a 1937-1938 environment, during which the world was headed to the largest global war thus far. What’s your theory on that?

Barros: It’s great to have peace, but you need to have all parties involved to want to have peace. What we see is a world where there are challenges to the current world order. We have Putin, who explicitly we have wants to create a multipolar world order, who seeks to conduct wars of conquest and normalize and legitimize wars of conquest. In Beijing, we have Xi Jinping preparing the People’s Liberation Army to be able to forcibly seize Taiwan and further reduce and expel American presence from Asia. We have the revisionists in the Middle East when it comes to Iran and that regime. What we see with the Russian invasion of Ukraine: the effort to try to do a war of conquest, change the borders with might. This is a referendum on the rules based international order that we established in 1945. The aggression is ongoing. The West at this point has not decisively committed to trying to defeat these threats.

What we’ve seen is there is a coalition an entente between Beijing, Tehran, and Moscow, where all of these people have different objectives. They have different ideologies, but what they have in common is they want to dethrone the United States, they want to dethrone the liberal international order and there they are united in that objective.

Similarly, what we had in the 1930s was a new string of isolationism, a retreat from wanting to have strong American involvement in the world, chronic ignorance and underinvestment in defense capabilities that are necessary to deter and, if necessary, decisively defeat these adversaries. We’re really at a time for choosing now, where I think larger-scale war is on the horizon, and we need to act decisively in order to deter it.

Meurmishvili: I hope you are wrong, but your analysis is sobering and terrifying. Thank you very much for your time!

Barros: Thank you very much for having me. Really, a pleasure.