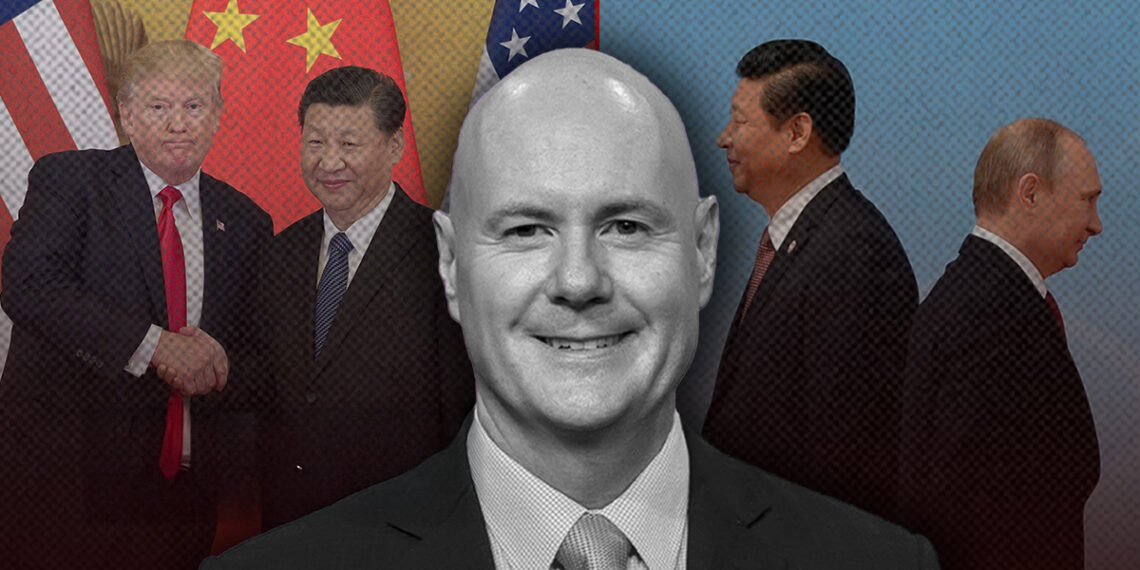

WASHINGTON (Independence Avenue Media) — China’s growing involvement in Russia’s war in Ukraine is drawing close attention from U.S. policymakers, according to Steve Yates, senior research fellow for China and national security at The Heritage Foundation.

Yates, former deputy assistant to Vice President Dick Cheney for National Security Affairs (2001-2005), warns that Beijing’s support for Moscow complicates efforts to pressure Russia toward peace.

“China has become much more involved in supplying energy and material to Russia that undeniably sustains that war effort,” he said, stressing that the U.S. cannot act alone. “Just as Europe needed to choose between deterrence of Russia and economic opportunity and dependence on Russia, they’re going to have to recognize that China is part of that same condominium.”

Beyond Ukraine, Yates frames China’s broader challenge as a new, multifaceted Cold War encompassing economic, technological, and strategic domains. He highlights the importance of strategic alliances and partnerships as alternatives to China’s transactional approach, including cooperation with the U.S., Japan, South Korea, and Europe.

Yates previously directed the China Policy Initiative at the America First Policy Institute, served as President of Radio Free Asia, and taught international business and politics at Boise State University.

Conducted on September 11, 2025, the following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kartlos Sharashenidze, Independence Avenue Media: Let me start with your general observation of U.S.-China relations right now, considering President Donald Trump’s statement last week that China, along with Russia and North Korea, is conspiring against the United States. Where do relations now stand?

Steve Yates, Senior Research Fellow, China and National Security Policy, Asian Studies Center at The Heritage Foundation: Well, for decades, our global leaders have been talking about [how] the interplay between China, Russia, and the United States comes from Cold War times through the [present] day. And that in [the past] decade or so, that has changed fundamentally, because there was pretty significant controversy surrounding Russia that was dominating international and domestic media coverage [of American] politics. And of course in the midst of all of that, there was the tragic reinvasion of Ukraine that kept the focus on that area.

Throughout that period, perceptions [of China] were changing as a result of unfair trade [policies], military modernization, aggression toward their neighbors, COVID and consequences of the fentanyl [crisis] that hit many, many American families, including my own. It wasn’t until a year or so into Russia’s [February 2022] invasion of Ukraine that the question of how much Beijing was helping Russia’s war machine began to get much attention. At first, it was sort of denied, and then it became sort of accepted wisdom. But some questions about how or what could be done about it [began to emerge].

But in the middle of all that, you also have organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, where China has tried to be a leader or center of gravity among a lot of former Soviet republics. And then there’s the BRICS gathering that talks about being an alternative structure in the world that is explicitly countering the American or Western institutions that dominated the Cold War and post-Cold War period. So, all of this has sort of colored things. But that statement that President Trump made was most interesting because he has been very open about willingness to meet and negotiate with [Russian President Vladimir] Putin, with [Chinese President] Xi Jinping, with Kim Jong-un of North Korea — all with the aim of trying to de-escalate tensions, trying to stop or avoid hostilities and find a more stable balancing point. Or at least that’s the theory that was thought to be [driving] the transition. But the president, as you no doubt have noted, has gotten a bit frustrated with Moscow in particular. And he’s sort of just beginning to prepare to have a more in-depth summit with Xi in the coming weeks or months.

Sharashenidze: Yes, and what do you see as the main goals the U.S. should have from this possible meeting? And how might you expect President Trump’s approach to China to differ from his first-term?

Yates: Well, in some ways, he has always believed in having leader-to-leader dialogue and negotiations. In doing so, he usually will say flattering words about the quality of his relationship with his counterpart. He will do things sometimes to shock the information environment, to try to make people unsettled and sort of read where things are moving, to try to pick targets for his negotiated deals.

The difference this time around, however, is that he has the experience of the first term, and that hasn’t dissuaded him from the imperative in his mind to have direct talks and negotiations. [For example], he has the experience of having negotiated a phase-one trade agreement that didn’t get implemented. He has the experience of President Xi not telling him the truth about the COVID pandemic, and there were dire consequences to that. He had [Xi’s] promise of cooperation to halt the flow of fentanyl precursor chemicals, and those, of course, exploded during the Biden years, and they’ve come down some with border enforcement in the United States, but still much more needs to be done. He also has the experience of negotiating, as he did with Putin. He felt like he had good rapport and thought he had good understanding with his counterpart, but now, perhaps, as has been the case with Putin, he has to assess, “am I really getting the action that the conversation led me to expect?” And with Putin, he’s expressed public dissatisfaction with his actions versus words. With Xi, we’re in an earlier phase of that conversation in this term.

And there is an Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit that will be hosted in the southern part of South Korea in late October. It would be a natural place for a bilateral meeting to occur with China. [And] when South Korean President Lee Jae Myung was in the Oval Office, [Trump] held out the possibility that the South Korean leader might join him on the plane to visit with Kim Jong-un in North Korea or fly with him to China for the conversation. So, those are the unconventional things that can come up when Trump is talking. But those have been all put on the map as possibilities.

Sharashenidze: What are your expectations if these meetings take place? You mentioned that President Trump has extensive experience with these leaders from his first term. But what has changed for these leaders over the past four years?

Yates: That’s a good question. There are some big fundamentals that have changed between the first term and the second term that don’t have to do with American politics, but to do with changes in the world. And of course Russia’s protracted war is a significant change. When Trump was in office before, we were not at a period of armed conflict. Of course, the United States is not directly involved in that current conflict but has been very directly involved in the policy and negotiations related to the conflict. And so, the whole environment around the relationship with Russia is very different in 2025 than it was in, say, 2017, when he came into his first term.

With China, it’s different in the sense that Xi is a later-term leader. There’s still this front-and-center question of unfair trade practices that President Trump has made a priority throughout and his desire to negotiate a more balanced, more fair deal. That’s continuity. But the change is that China has been very aggressive toward its neighbors. It has encroached upon the Philippines in ways that are quite surprising for long-term Asia watchers. Its military exercises that encroach upon Taiwan are much more frequent, much larger scale, and much more provocative than things that occurred in the Biden term and in Trump’s first term. And so, there’s an escalated sense of tension in both of those relationships.

The big question for President Trump in trying to have talks with Xi is there’s a pretty wide range of very big issues where China really needs to move — and the president needs to get China to move. The top of the list for me is fentanyl. How do you justify letting chemicals into the world, illicitly, that are the number one cause of death for 18-to-35-year-old Americans? That’s just an unfathomable problem, and China must stop that. But how does the president get that to stop? He has to talk about trade; he has to talk about China’s role in Russia’s war machine and how to change that. And he’s threatened secondary sanctions on China. And if you threaten them, you have to back up [those threats] and do it or it becomes an empty [threat]. So, those are the hard things on the president’s ledger. Now his leverage with China is that the United States remains the biggest, most robust consumer economy on the planet. And China cannot survive healthily without reliable access to it. So, the president does have some leverage and some cards.

Sharashenidze: You mentioned Ukraine several times. From your perspective, what are China’s strategic interests in Russia’s war against Ukraine, and what does this mean for Washington’s policy toward China? What does the U.S. need to do in this situation regarding Ukraine?

Yates: Right. Well, I do think that the president needs the Chinese to believe that secondary sanctions will apply to them, or I don’t believe they will change their strategic behavior. And their strategic behavior at the beginning of the war on Ukraine was one of China sort of playing all sides.

They were everyone’s friend and mostly they wanted to profit when the conflict was over. But Ukraine has natural endowments that are of value to China, and [they] want to preserve access there. And there was a relationship with Russia that they wanted to preserve. So, again, they were sort of playing all sides and, as this has gone on — and I can’t speak to what Ukrainian perceptions are of China’s role — but China has become much more involved in supplying energy and material to Russia that undeniably sustains that war effort.

So, all of this gets in the way of whatever pressure that sanctions might have on Russia. It also means that the president needs Europe to make a choice. That it can’t be America alone trying to press China, just as Europe needed to choose between deterrence of Russia and economic opportunity and dependence on Russian [energy]. They’re going to have to recognize that China is part of that same condominium. And if [Europe is] serious about trying to get Russia to stop, they’re going to have to join the United States and others in pressing Beijing to pull back from that material assistance. And if we don’t do that, I fear that we’re in for a long grinding process where Putin will not get serious about peace.

Sharashenidze: You mentioned tariffs. We’re now seeing that President Trump is expecting the EU to impose tariffs on China as well. We’re also seeing an agreement where NATO and EU countries buy U.S. weapons for Ukraine. What are your expectations for the EU? Do you believe Europe is ready to take on these responsibilities?

Yates: The core principle is that it should be Europeans doing all they can to help other Europeans so that America can play a supporting role. I’m not taking anything away from the need, but America has to do things in other theaters where Europe cannot have [as] decisive [an] impact. In order to balance those risks and responsibilities, I think that’s where the principle of Europeans doing more for themselves and for other Europeans has to apply. And I think there has been progress in that area.

It’s sort of like what happened with Iran-related sanctions over the years when the U.S. and Europe were unified in trying to pressure the Iranian regime [over its] nuclear program. But Russia and China were doing business with Iran that made those sanctions and that [coordinated effort to isolate Iran] less effective. And so, with Europe, we need them not to be a net negative in trying to pressure Beijing’s [support for] Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. We don’t have high odds of success in this, I would say, because China and Moscow operate under their own logic. They may think that they’re insulated from sanctions, but I think it’s a “must-try.” And I would like to believe that like-minded democracies could be unified in making that work.

Sharashenidze: Many experts say that what happens in Ukraine sets an example for China regarding Taiwan. So, what does this mean from the U.S. perspective? For an American strategy toward China?

Yates: I do have friends who speak in terms of drawing parallels between the Russia-Ukraine situation and the China-Taiwan situation. I don’t subscribe to that point of view in part because I see a very separate logic in each. The one is an active conflict; the other is a conflict we hope to avoid. There are, however, some lessons from the Ukraine experience that I think very correctly apply to the way Taiwan and its friends should be thinking. Everything from the failure of deterrence prior to [Russia’s February 2022] invasion to the lessons from drone warfare to cyber and other capabilities. I think we’ve learned that there is a different form of warfare at play and that we need to have a different form of deterrence, perhaps, if we’re going to keep China from trying to [invade] Taiwan. But the problem from the East Asian point of view is that China had sought to impose its will on Taiwan long before there was a question of whatever [post-Soviet] Russia’s relationship was with Ukraine. And I don’t think that the Communist Party of China would be dissuaded from that long-term way of thinking regardless of the direction the conflict between Russia and Ukraine would go. I still think it’s important that we do the right things [in order] to do the most we can to stop the killing and try to preserve some sense of peace and progress with the Ukraine situation. But I don’t think success [for Moscow] in Ukraine guarantees success [for Beijing] in Taiwan, and I don’t think failure in Ukraine [for Moscow] guarantees failure [for Beijing] on Taiwan. So, I don’t know if that’s too convoluted, but I do know that people in Taiwan follow the situation in Ukraine quite closely and they feel a sense of common cause. But just as an analytical matter, I don’t see one as determinative for the other.

Sharashenidze: When it comes to strategic partnerships with China, all three South Caucasus countries now have such relationships. Georgia’s strategic partnership with the U.S. is currently suspended, but in 2023, Georgia became a strategic partner of China while already being a U.S. partner. China also has a comprehensive strategic partnership with Azerbaijan and, just recently, Armenia became a strategic partner of China as well. How do you see this trend? Looking ahead, do you think it will be possible for these countries to maintain close ties with both the United States and China at the same time, or will there be a conflict of interest?

Yates: It’s a good question. I don’t believe it is possible in the long term until there’s a change in the way China conducts its interactions. So, on the surface, it can look very friendly. And in a transactional way, they can bring economic opportunity. I think, though, that the right response by the United States and a lot of European partners — and maybe even some East Asian partners — is for us to bring economic opportunity to those countries and regions in a coordinated way. To give them an alternative. Because I think the quality of the cooperation they could have with Japan, Korea, Britain, maybe Germany, France or Poland, together with the United States, that’s a bigger, broader, more sustainable opportunity that they probably would welcome. But in the absence of the United States and others doing that, they’re saying yes to the proposition China makes. Maybe they like it. Maybe that’s what they want. Or maybe they feel like that’s just the best opportunity that’s being put before them, so they’re accepting it. That’s why I think it’s imperative for us to find some sustainable peace in the Ukraine situation for our leadership to be able to focus in these other areas too, to try to bring opportunity.

Sharashenidze: I’d like to ask you about China’s strategy. I mean, after Georgia signed its strategic partnership agreement with China, Georgian government officials said, “We have a partnership with the U.S., but we don’t get visa-free travel or free-trade agreements. With China, we actually get these concrete benefits.” How does China use these kinds of tactics? And how central is this approach to China’s broader strategy in winning over countries like those in the South Caucasus?

Yates: Well, the Chinese government does its homework. I can’t criticize them for that. And in their homework, they will find areas where some of our partners around the world are unhappy about us not offering certain opportunities or are being distracted by other areas of the world and they might feel neglected. And the China leadership can be opportunistic. I can’t blame them for seeking opportunity when we might be distracted or are not in the position to offer what is being sought at the moment. But what I can blame them for is, say, like with their Belt and Road Initiative, where they’ll go out and they’ll spend what seems like big money, but after it’s spent, it’s gone. And if it doesn’t lead to sustained employment in the target country and there’s questions of corruption or quality issues with construction that come later, it helps the government that’s in power, but the government that comes after that suffers and so do the people. And so, I think there’s a track record where opportunistic governments might choose the China option, but then they’re burned over time and people need to learn their own lessons on that front.

So, China does use — “deception” may be too strong a word — but they’re selling their offer, and it might not be the whole story. It’s more of a short-term transaction, not a long-term commitment. So, I think that’s where the United States, if it can get free of the high-pressure priorities that are taking so much time, would love to find ways to pursue those kinds of opportunities with some of these areas where, we’d have to confess, do get somewhat neglected.

Sharashenidze: Multiple times, you mentioned a new Cold War. This is something we see discussed a lot regarding the current situation. So, what are the main components of China’s strategy in this so-called new Cold War?

Yates: The Heritage Foundation did put out a product that defined a comprehensive challenge that we called a Second Cold War. Not everyone accepts the way we talk about it, but I would defend the way it was talked about in the following way: I think that the government of China has engaged in Cold War-like behavior for quite a long time. And that just means that during the Cold War, there was a comprehensive competition. There were massive efforts to take advantage at our expense on both sides. And with China, there are increasing signs of that. And that the challenge is more comprehensive than in traditional foreign policy terms. We have our social fabric in our country challenged by economic hollowing out, but also by chemical and biological warfare, whether it’s COVID or fentanyl. We have competition for alliances and partnerships that are being challenged and weakened. And there’s this effort to try to undermine what the United States is trying to do that is consistent with a Cold War competition if that hopefully stays cold and doesn’t lead to a hot conflict. That’s the construct that’s being talked about. And I think the more people look at it, they’d say, “oh, it probably does, as they say, look like a duck, walk like a duck, it probably is a duck.” And so it looks like a Cold War, seems like a Cold War. If you don’t want it to be one, then what are you doing to contribute to an alternative? And that’s where I think President Trump and President Xi have their work cut out—primarily for Xi to say how China seeks a better path with the United States and its neighbors.